The Secret City

Growing up in a city built for war and headquarters of the Manhattan Project.

This excerpt is from a memoir I’m writing about healing from traumas and experiencing spiritual awakenings that led to transformations. Growing up in the Secret City of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, one of the three cities in the Manhattan Project, I was groomed to become silent and not talk about feelings and emotions, but to value being good, secrecy, loyalty and compliance.

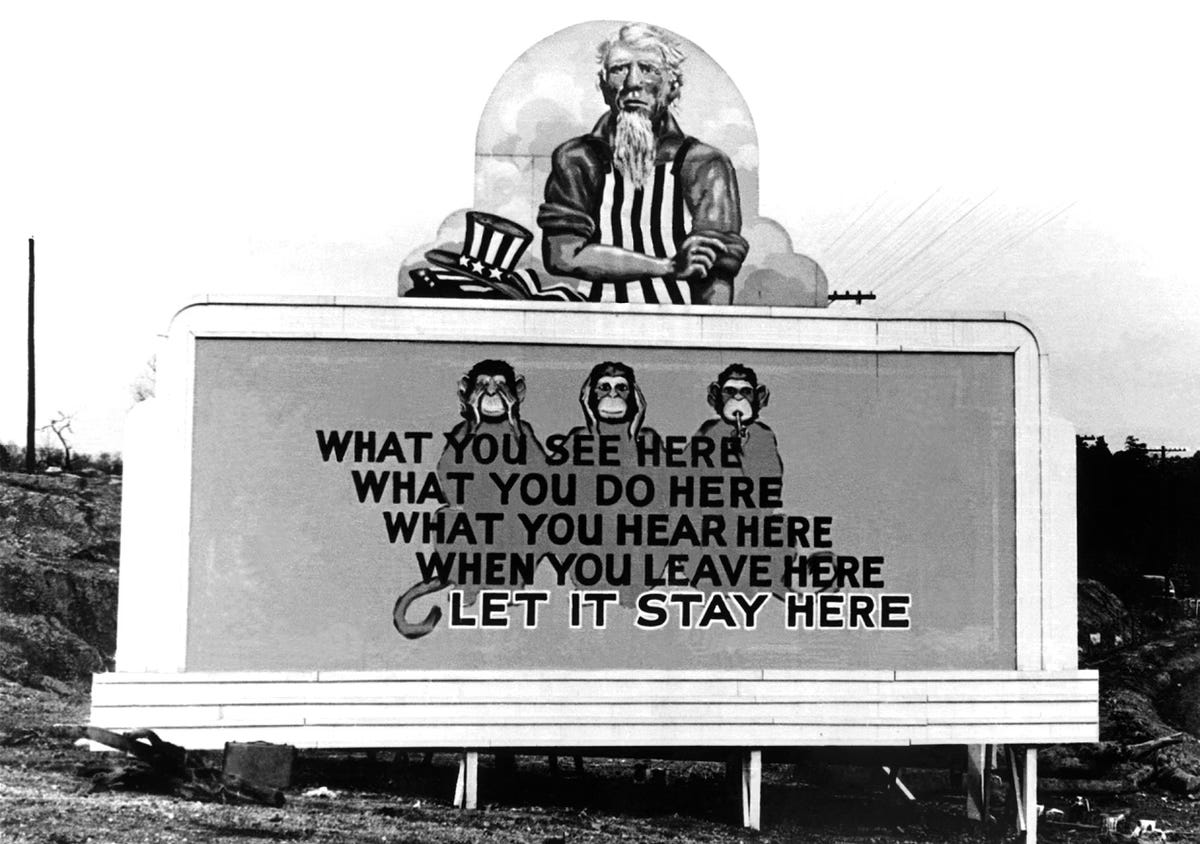

I was born in a city so secret it wasn’t even on a map until I was seven. Billboards around the city warned: What you see here, what you do here, what you hear when you leave here, let it stay here, and Protection for all. Silence Means Security.

Ed Westcott, DOE

In 1942, the government secretly acquired 60,000 acres of land in East Tennessee by eminent domain, displacing 1,000 families (at least 3,000 people), including farmers and Native Americans, from 800 parcels of land where they’d lived for generations in a seventeen-mile-long valley in the Appalachian Mountains. These people were forced to abandon their homes and land with little notice or compensation.

Black Oak Ridge's valley was isolated but had access to water, electricity, and nearby railroads. The U.S. Army covertly built industrial plants there. With the promise of jobs, the new city (later named Oak Ridge) drew tens of thousands of new families to work.

During the construction of the plants, the Federal Government provided everything for the employees—free housing, healthcare, schools for their children, food from grocery stores and cafeterias, and other social needs—all in exchange for their silence about what they were working on.

Like everyone who lived in Oak Ridge early on, my grandfathers brought their families there because they were promised a good job, a house, and provisions.

Grandad Barker, my father’s father, had been a safety engineer for the U.S. steel mines in Lynch, Kentucky. He moved my grandmother to Oak Ridge after he got a similar job at the uranium enrichment industrial plant (K-25).

My dad, James Barker, their only child, attended his first two years at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky, the first integrated, co-educational college in the South. Students worked at the college in exchange for tuition. Dad transferred to the University of Tennessee as a junior and graduated with a degree in business.

My mother’s parents moved to Oak Ridge when she was a junior in high school after her father got a job at K-25. Her father was a barber in Lenoir City before moving my grandmother, Pearle, my mother, and her brother to Oak Ridge.

“We were so poor when we moved there. My mother worked, but we didn’t have money for bras,” my mother told me. “We tore up old sheets to tie around ourselves.”

Ed Westcott, DOE

Oak Ridge had a mix of brilliant scientific minds and plain old country folk. People recruited to Oak Ridge in its early days said it went from Dogpatch (a fictional cartoon town from the Lil Abner comic strip featuring a clan of hillbillies) to a city built for war with 75,000 people enclosed behind a barbed wire fence with seven gates patrolled by armed guards.

Why all the security? During World War II, Oak Ridge was one of three sites in the Manhattan Project, the secret program responsible for developing the atomic bomb. The government built nuclear facilities at Oak Ridge, Tennessee (Site X) and Hanford, Washington (Site Y), with the main assembly plant built at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Oak Ridge had one of the largest bus systems in the country, and electric consumption outpaced New York City during peak production. Nine cafeterias, five restaurants, and three lunchrooms provided food for the workers and their families. Thirteen supermarkets were for those who wanted to cook at home, and nine drug stores sought to provide anything else people might need. In exchange, those people gave away their civil liberties.

People who worked on the Project, including my father, believed their work was mission-critical to end the war. Dad was proud of his job because his education had garnered him a middle-class wage and a white-collar job.

“Everybody knew something was going on, but we didn’t know what it was,” Mom told me. “We knew the government was building something secret there.”

Ed Westcott, DOE

The Project employed what Oak Ridgers called “creeps”— government agents — to spy on residents and visibly enforce security protocols. Someone was always watching. It was said that one in four people in Oak Ridge was an FBI informant.

In a dystopian society, “Citizens perceived to be under constant surveillance, have a fear of the outside world. Citizens live in a dehumanized state. The natural world is banished and distrusted.”*

In 1947, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) was finished and became home to the X-10 Graphite Reactor that produced significant amounts of the plutonium-239 used in nuclear weapons.

Oak Ridge was a total exclusion area, which meant you couldn’t enter without military permission. The government even secured air space over that valley as a no-fly zone.

On the roads to the plants from town, billboards read: Loose Lips Sink Ships, and Your Pen and Tongue can be Enemy WEAPONS. Watch what you write and say.

The army placed these billboards near each of the seven guard gates, where military police boarded buses and checked all the passes. Secrecy continued to be part of the code of living there during the Cold War following WWII in the late 40s and even persists today according around toxic waste stored in areas around Oak Ridge. 1

“In high school, my class went on a field trip to Big Ridge State Park,” Mom said. “I lost my Oak Ridge ID badge while we were there.” She laughed as she told me this story.

“I wondered how I’d get back through the guard gates without it. The bus driver waited while I looked but couldn’t find it. We finally had to leave. Then I quickly hatched a plan to get into Oak Ridge.” She leaned in and whispered to me conspiratorially,

“I decided to lay down on the long seat across the back of the bus, and my girlfriends sat on top of me so the guards wouldn’t see me. It worked, and I made it through the guard gates!”

I laughed and realized I would have done the same thing. So would Nana Pearle, my grandmother on my mom’s side.

During the war, many young women who were high school graduates were recruited to work at the plants because they were compliant and would do what they were told without questioning authority.

That wasn’t the life my mother wanted. After graduating high school, she put herself through the University of Tennessee. She wanted to study Interior Design, but things changed when she met my father.

“Your father and I met on a blind date. One of his UT fraternity brothers fixed us up,” she fondly recalled. “Your dad’s fraternity, Pi Kappa Alpha, chose me to be the Dream Girl of the fraternity. I was so proud and honored to be chosen. I got free lunch at the fraternity house every day. A free meal was a big deal because I had little money. I supported myself through college, waiting tables and serving breakfasts at the UT Student Center.”

“If I’d pursued Interior Design, it would have been a five-year program,” Mom told me. “I wouldn’t have been able to get married, work in interior design, and have a family simultaneously.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” I said.

“Your father had a big job, and we wanted a family. It wasn’t what women did back in my generation. But I always dreamed of working with color and interiors,” she told me.

I felt sad for her and decided that would never happen to me. I would work in a career I loved, married or not.

Mom graduated from the University of Tennessee with a degree in home economics in 1950. But she always yearned to be more and use her creativity. She wanted to design beautiful interiors. She took us to bargain basements, where we waited while she sorted through bins of fabric and damaged goods, finding colorful pillowcases for our beds. We hated going shopping with Mom because we’d be out for hours. Whatever we wanted didn’t matter when a bright fabric or a curious pattern caught her eye.

Growing up, I witnessed my mother’s sadness because she couldn’t follow her passion. I internalized the message: If you get married and have a family, you can’t have a career. The dominant theme in culture at the time was to get married. I watched Mom suffer from ’50s cultural programming that told women they couldn’t simultaneously have a job and children. Advertising glorified the housewife and consumerism.

Mom put her Home Economics degree to good use and was an excellent cook and seamstress. She had four children, and my father was the love of her life. She provided a good home, was a great cook, and sewed our clothes. Yet, I know she yearned to have a bigger life.

My father joined Union Carbide’s Nuclear Division in 1951. One evening a week, he drove to the University of Tennessee in nearby Knoxville to take courses for his MBA. After he graduated, Dad became the Director of the Employee Relations Division at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (X10), where he worked until he became the Director of Personnel.

Although Dad was introverted and quiet, his peers respected him because he excelled in working with people. He thrived recruiting Ph. D.s and nuclear physicists from university faculty and graduate students from Columbia, (UC) Cal Berkeley, MIT, Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and the University of Chicago. Records once showed a greater concentration of Ph. D.s at the plants than anywhere else.

“To be successful, you have to go to college and get a good education,” Dad told me once after we ran an errand to pick up his materials from the United Way of Oak Ridge, where he was on the board.

“When you get a job, you have to work hard. When you need volunteers, ask the busiest people you know because they’ll get the job done,” Dad said.

I knew Dad did something important, but it wasn’t until I had lunch with him in high school that I began to understand what was happening at the plants, and my concern turned to safety.

I felt proud of my father as we walked towards the cafeteria. Dad was a handsome man and a sharp dresser. Each morning, after he got out of the shower, he did stretching exercises before dressing. He put on a fresh-starched white shirt, tie, and suit jacket. He was proud his college education gave him the ability to have an excellent job to provide for his family.

Dad was a people person, and everyone we passed was friendly to him. I knew he was deeply respected and had a big job, but he was often stressed out. But I admired and respected him and didn’t want to disappoint him.

Walking to the cafeteria, I saw a knee-high chain fence running next to the sidewalk, with signs saying, “Caution Radiation.”

“Dad, radiation is dangerous. How often do they check you,” I asked as he opened the door to the cafeteria. As we walked in, he said, “Our badges are checked monthly for radiation exposure.”

“What about all the nuclear waste? Where does the government put it?”

“The government is storing it safely in the salt flats of the Yucca Mountains in Nevada.”

“How could nuclear waste be safely stored? I wondered. I was not pro-nuclear power like my father, but I never said anything.

I knew Oak Ridge would be a target if there were a war. None of my teachers ever expressed fear, and none of my friends or family ever mentioned it. We were more concerned with our friends and social schedules in high school, but I planned to leave after high school.

I never felt anyone was better or less than me, like my father, who treated everyone respectfully. But my mother taught me to give to less fortunate people than us.

“A low-income family lives near the lake house with five little boys,” Mom told us. “They run around barefoot in the cold weather. They don’t have coats and winter clothes. You can pick out a small gift for each of the boys,” Mom said as we pulled up to a Dollar Store.”

My sister and I got out of the car and ran inside. We chose small bags of army guys to give each boy.

We drove down the parallel roads called ‘hollers’ that Dad used to drive to work from the lake house. We passed Man Holler Road, then turned on Suck Egg Hollow Road, where the family lived. The little boys ran out to the car excitedly. Mom got out and gave them the toboggans and gloves she bought each boy. Then she gave each boy a bag of army guys.

When I had my son, I baked pies each Thanksgiving. My son and I took them to Mission, where I showed him how I cared for the less fortunate, just like my mother.

At Oak Ridge, however, during the Manhattan Project and throughout the Cold War, the rules and expectations were obvious. You did not speak of your work to anyone or question rules, procedures, or even the objective of your work. The punishment was treason and death, but only two people were executed for their roles in a Soviet Union Espionage plot to gain top-secret US intelligence regarding the Manhattan Project - Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted of treason in 1951 and executed.

People who worked on the Manhattan Project and later during the Cold War, including my father, believed their work was mission-critical to end the war. Everyone who worked in Oak Ridge was bound by secrecy not to talk about work to anyone. You did not question anything --authority, procedures, regulations, or even the objective of your work.

“Everybody knew something was going on, but we didn’t know what it was,” Mom told me.

“Your father and I met on a blind date. One of his UT fraternity brothers fixed us up,” she fondly recalled. “Your dad’s fraternity, Pi Kappa Alpha, chose me to be the Dream Girl of the fraternity. I was so proud and honored to be chosen. I got free lunch at the fraternity house every day. A free meal was a big deal because I had little money. I supported myself through college, waiting tables and serving breakfasts at the UT Student Center. ”

My father joined Union Carbide’s Nuclear Division in 1951. One evening a week, he drove to the University of Tennessee in nearby Knoxville to take courses for his MBA. After he graduated, Dad became the Director of the Employee Relations Division at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (X10), where he worked until he became the Director of Personnel.

Although Dad was introverted and quiet, his peers respected him because he excelled in working with people. He thrived recruiting Ph. D.s and nuclear physicists from university faculty and graduate students from Columbia, (UC) Cal Berkeley, MIT, Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and the University of Chicago. At one time, history records show a greater concentration of Ph. D.s at the plants than anywhere else. Most citizens were “To be successful, you have to go to college and get a good education,” Dad told me after we ran an errand to pick up his materials from the United Way Oak Ridge, where he was on the board.

“When you get a job, you have to work hard. When you need volunteers, ask the busiest people you know because they’ll get the job done,” Dad said.

When I left Oak Ridge at age nineteen, I kept two secrets in my subconscious out of my conscious mind:

“You can’t have love and a family and fulfill your dreams,” and my father believes, “Don’t depend on anyone. You have to take care of yourself.”

My life up to age 65 was driven by the belief that I had to maintain my independence and care for myself. I’m learning to let go of work and allow myself to depend on my husband, John.

Now, over to you. I’m curious how you feel reading about life in the cold-war era and living in fear of the Russians? How does this make you feel reading it? As someone who grew up in this environment, it was normalized.

XO, Sherold